The Vesterheim Norwegian Museum in Decorah, Iowa has posted a tribute to Beatrice Tonnesen on the blog on its website. The posting contains an article and photos from an exhibit titled Innovators & Inventors open at the museum through May. Here’s the link:

Category Archives: Lois

Who was Trentini? A Fox or Tonnesen Pseudonym?

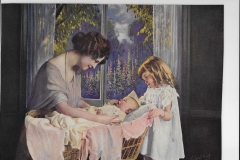

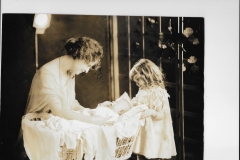

Over the years, I’ve noticed prints bearing a resemblance to the works of Beatrice Tonnesen or R.A. Fox (painting as “DeForest”) in antique stores or online, only to discover on closer inspection that they were signed “Trentini.” This remained merely a curiosity until a couple of years ago, when I spotted one featuring a little girl and a baby who can definitely be found in several prints and photos by Tonnesen.

I bought the print, titled “Playing Mother,” compared it to images in my Tonnesen files, and found that it matched a photo created by Tonnesen in the early 1920s. The original photo is owned by the Oshkosh Pubic Museum.

Since then, I have found two other prints signed “Trentini.” One, titled “Sweethearts,” features a girl shown in a print by DeForest, titled “Strictly Confidential,” along with a boy who, I believe, appears in a print titled “Miss Coquette,”signed “Tonneson. This print originated as a photo by Tonnesen, also owned by the Oshkosh Public Museum.

The other Trentini print, titled “Flowers for Mother,” features a girl who may be the same one as in “Sweethearts” and shows a very Fox-like house in the background.

In addition to all of this intrigue, there’s the Trentini signature, which employs the long-tailed “n” extending way below the other letters – just as both Tonnesen and Fox are known to have sometimes used in their signatures.

So I now wonder if Trentini is just another of the 1920s era illustrators who painted from Tonnesen’s photos, or if Trentini is another pseudonym for either Fox or Tonnesen.

To try to determine if there was a real artist named Trentini in the Chicago area (where Tonnesen and her models lived and worked), I consulted family trees, newspapers, census reports and city directories. I found a few people named Trentini, but no one who listed their occupation as “artist” or anything similar and no one who seemed to have a connection to the art or publishing community. For now, I lean toward the theory that “Trentini” is a pseudonym. But whose?

(Shown: Prints signed Trentini and signatures of Trentini, Fox and Tonnesen.)

© 2020 Lois Emerson

Playing Mother

Sweethearts

Flowers For Mother

Art by L. Goddard: More Woolfenden than Ingerle?

On this blog, I display and write mostly about the work of Beatrice Tonnesen, whose creations of photo illustration art graced America’s calendars during the early part of the twentieth century. But Tonnesen wasn’t the only one using this technique. The prints signed “L. Goddard” provide the most prominent example of photo illustration art during that same time. Because of the similarities and inevitable comparisons and, sometimes, the apparent connections between the two, I have found myself researching and collecting Goddard as well as Tonnesen.

Collectors routinely describe the L. Goddard signature as representing a collaboration between Leonora Woolfenden (1877-1955) as photographer and Rudolph Ingerle (1879-1950) as artist. But I’m not so sure that L. Goddard always involved Ingerle. Over the past several years I have questioned- on this blog and in my ebook “The Secret Source: Beatrice Tonnesen and the Calendar Art of the Golden Age of Illustration”-the extent to which Woolfenden might have acted as both photographer and illustrator and if she, at times, might have painted from the photographs of others (Tonnesen being one of them, but that’s another story).

Here’s why I began to wonder. First, Woolfenden’s maiden name was Goddard. Since her first name was Leonora, she actually was L. Goddard until she married Mr. Woolfenden in 1903. She started out at the Arthur Studio in Detroit in the 1890s. Primarily known as a photographic studio, it nonetheless turned out artwork signed Arthur, Arthur Studio and James Arthur (the owner) through at least the early 1920s. These works are often found on calendars and other advertising items, as well as prints framed for hanging. Though James Arthur died in 1912, the studio continued to operate; artwork attributed to Arthur continued to appear; and census reports and city directories continued to place Woolfenden in Detroit as an “artist” until 1930.

In addition, around 2010, I found a publisher’s blurb from a 1920s calendar print titled “Moonbeams and Moon Dreams” that states it is “From an original painting by Leonora Goddard.” It goes on to say that she “first turned her attention to art in photography and “…later developed her talent for water color and oil painting from photographic models.”

Fast forward to December, 2018. I noticed that Grapefruit Moon Gallery, one of my favorite sources of vintage art, had begun listing prints signed L. Goddard accompanied by their source photographs at auction on Ebay. I was able to obtain two sets of them. The first print, titled “The Love That Never Fails,” was a charming scene of a mother and daughter gazing adoringly at a baby in a bassinette. The matching photo was attributed to Woolfenden on the back. The second print, titled “Where Love Abides,” depicted a loving couple watching their son and daughter at play. But the accompanying source photo was attributed not to Woolfenden, but to a prominent New York-based photographer named Joel Feder! Not only that, but Grapefruit Moon Gallery also displayed a second L. Goddard/Joel Feder set that I failed to obtain, proving that “Where Love Abides” was not the only L. Goddard print derived from a photographer other than Woolfenden.

Meanwhile, Rudolph Ingerle is known to have had a career as a painter outside of his work with Woolfenden. He was primarily a landscape artist, but also did some photo illustration work using his Ingerle signature. I cannot fathom him painting from a photo by Feder and then signing Leonora Woolfenden’s maiden name to it instead of his own. But I can well imagine Woolfenden signing her maiden name to a work that she herself painted from a photo by Feder.

I don’t know the exact source of the widespread belief that L. Goddard represented a collaboration between Woolfenden and Ingerle. From what I have heard and read, a publisher’s blurb naming Woolfenden and Ingerle as the artists behind the signature was found on a calendar displaying one of the many prints of Indian maidens signed L. Goddard. Still, I do believe it’s likely that the L. Goddard signature didn’t always involve Ingerle, but was sometimes simply Woolfenden signing her maiden name to something she painted from a photograph, whether hers or someone else’s.

Accompanying this post are images of the two print/photo sets signed Feder, Woolfenden and L. Goddard and an example of a photo illustration signed R. F. Ingerle. The piece by Ingerle had to be photographed under glass. I apologize for the reflections.

© 2019 Lois Emerson

Glimpses of History: These Pieces of Art Are Unusually Informative

In the last few months, I’ve been lucky enough to find three uniquely informative creations by Beatrice Tonnesen. It’s always a treat to find items I haven’t seen before, but it’s especially rewarding when they turn out to contain information that illuminates my glimpse into how she worked.

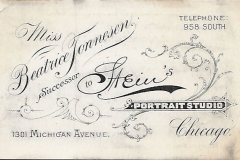

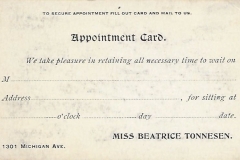

-The elaborate business/appointment card,shown here front and back,must date back to about 1896, when Beatrice and her sister Clara, who functioned as Beatrice’s business manager, moved from Menominee, Michigan to Chicago to take over the studio of the prestigious society photographer S.L.Stein (1854-1922). Since the card touts Beatrice as Stein’s successor, it’s reasonable to assume it was created early in the life of the studio which became known as the “Tonnesen Sisters.” Tonnesen Sisters Studio flourished and gained nationwide fame until about 1904, when it was abruptly announced the studio was bankrupt, with claims by creditors totaling $650! Subsequently, Clara returned to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where the sisters had grown up. Beatrice, apparently, continued successfully, working solo until about 1930, likely at first from her home in Chicago and, later, from two more studios in the city.

-The beautiful 1922 calendar shown here is a perfect example of the popular “Cult of Motherhood” theme that exalted home and family in the art of the early 20th century. Besides producing a beautifully tinted photograph on a quality, heavy cardboard mount, the publishers provided a very thorough identification -much appreciated by me- of the artwork. Titled “Baby is King” and copyrighted in 1920 by American Artworks Coshocton, Ohio, it is identified as a “Study by Tonnesen Studios.” (The use of the word “study” in popular calendar art is interesting. I’ve seen only one other photo by Tonnesen described that way.) This photo was probably taken around 1917, based on the presence of one of Tonnesen’s favorite child models, Virginia Waller (1913-2006). Virginia modeled, mostly for Tonnesen, from about 1916-1920. The woman in the photo, believed to be nationally-known professional model Adelyne Slavik (1892-1984),often portrayed Virginia’s mother.

-The third item is an interesting advertising piece for Bayerman Furniture and Undertaking(!), with a photo on glass, mounted on wood, with a thermometer and a 1929 calendar. The photo shows a boy and girl who appeared in a series of photos featured on calendars during the late 1920s and early 1930s. I had been wondering when the photos of this couple were actually taken, because newspaper ads indicate that Tonnesen had begun selling her photographic equipment around 1927 in preparation for her retirement in 1930. So I found it very helpful to discover the tiny copyright date etched at the bottom right in this glass: 1926! Both the Oshkosh Public Museum and the Winneconne (WI) Historical Society have original photos from this series.

Copyright 2018 Lois Emerson

Tonnesen’s Advertising Art: Four Enchanting New Finds

Over the last several months, I’ve been concentrating on getting the site maintenance needed to continue to present this blog. With the help of an outside contractor, we have managed to get the galleries back up and running and restored images on individual posts that, for reasons not understood by me, had simply disappeared. With that technical work mostly behind us, it’s fun to get back to simply presenting Tonnesen’s enchanting creations! Here are four newly-discovered examples of her advertising art. In this order, they are:

-Ice cream-themed advertising fan for Coffey’s Pharmacy, Plymouth, New Hampshire. This woman appears in several of Tonnesen’s archived photos, sometimes wearing this same dress, around 1920. The dress and the roses are seen often in Tonnesen’s work. The photo seems to have been superimposed onto the illustrated background.

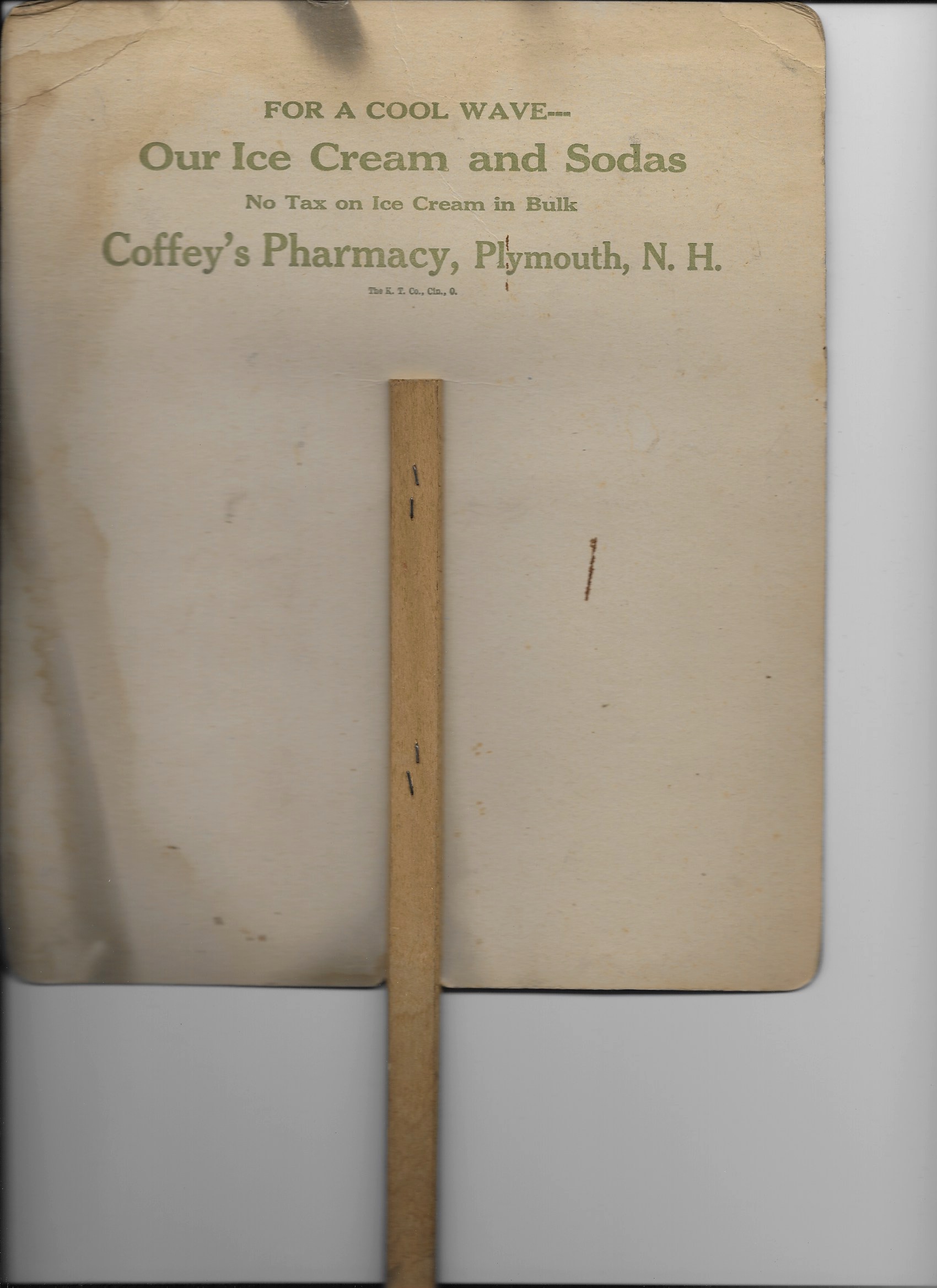

– Back of the Coffey’s Pharmacy fan.

– 1927 calendar featuring a print titled “The Idol,” advertising the Maier Plumbing Co. All of these models appear in confirmed photos by Tonnesen in the early 1920’s. The stool, doll and Mom’s dress are all Tonnesen props. The scene outside the window is typical of other scenes/backgrounds in Tonnesen’s work, making me wonder if she did the illustration as well as the photography.

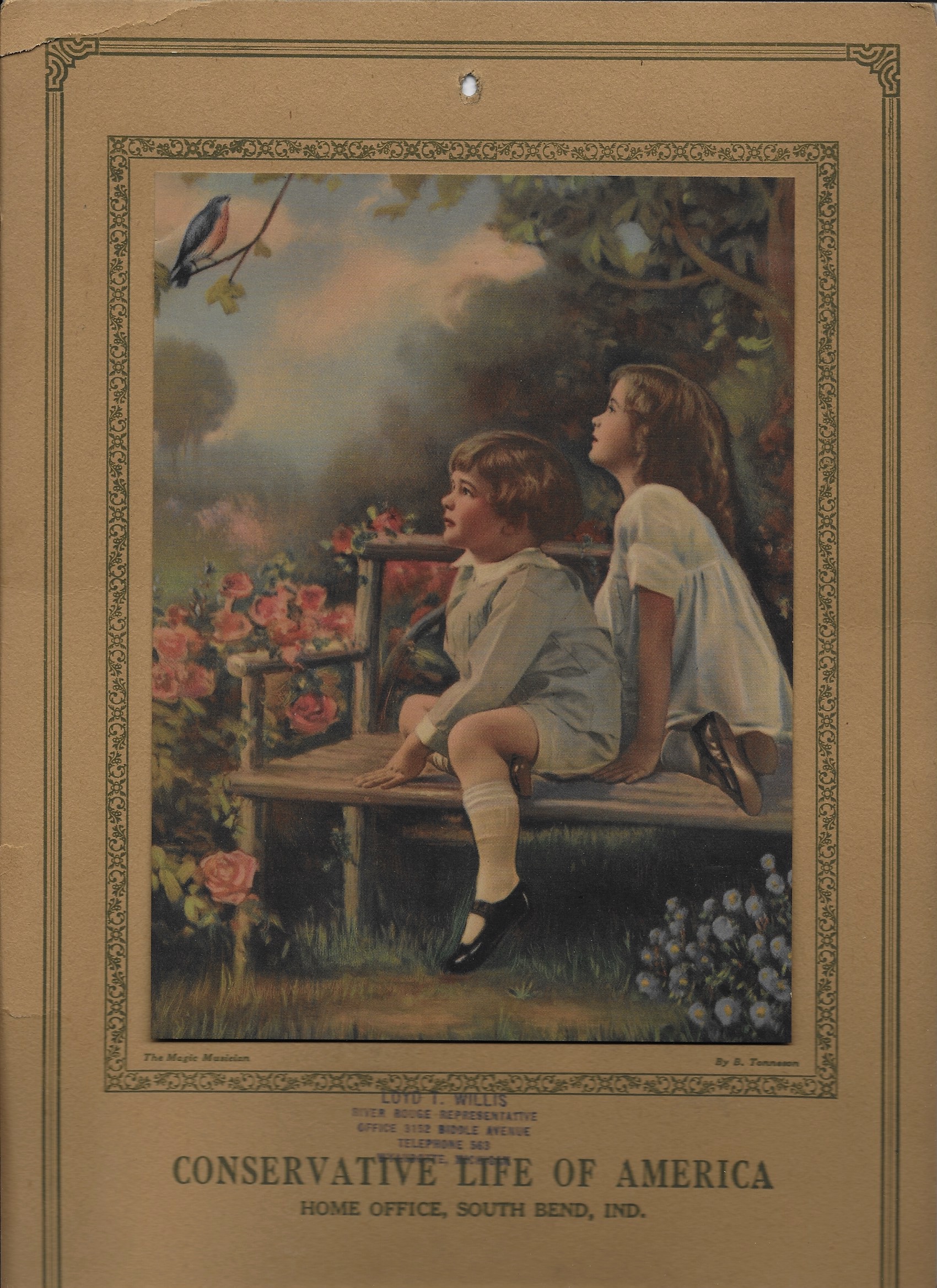

-“The Magic Musician” shown on a 1931 calendar advertising Conservative Life of America, attributed “B. Tonnesen” on the calendar mat. This print is somewhat of a mystery to me. Outside of the fact that the boy can be found in other confirmed photos by Tonnesen taken in the early to mid-1920’s, I can’t find anything else that I would describe as “Tonnesen-like.” Until I saw the attribution, my guess was that it was done by Adelaide Hiebel (1885-1965), who did a series of prints featuring children and bluebirds. That was a very successful series, so it’s possible that Tonnesen decided to jump on the bandwagon. It’s also possible, though unlikely, that the publisher made an error in the attribution.

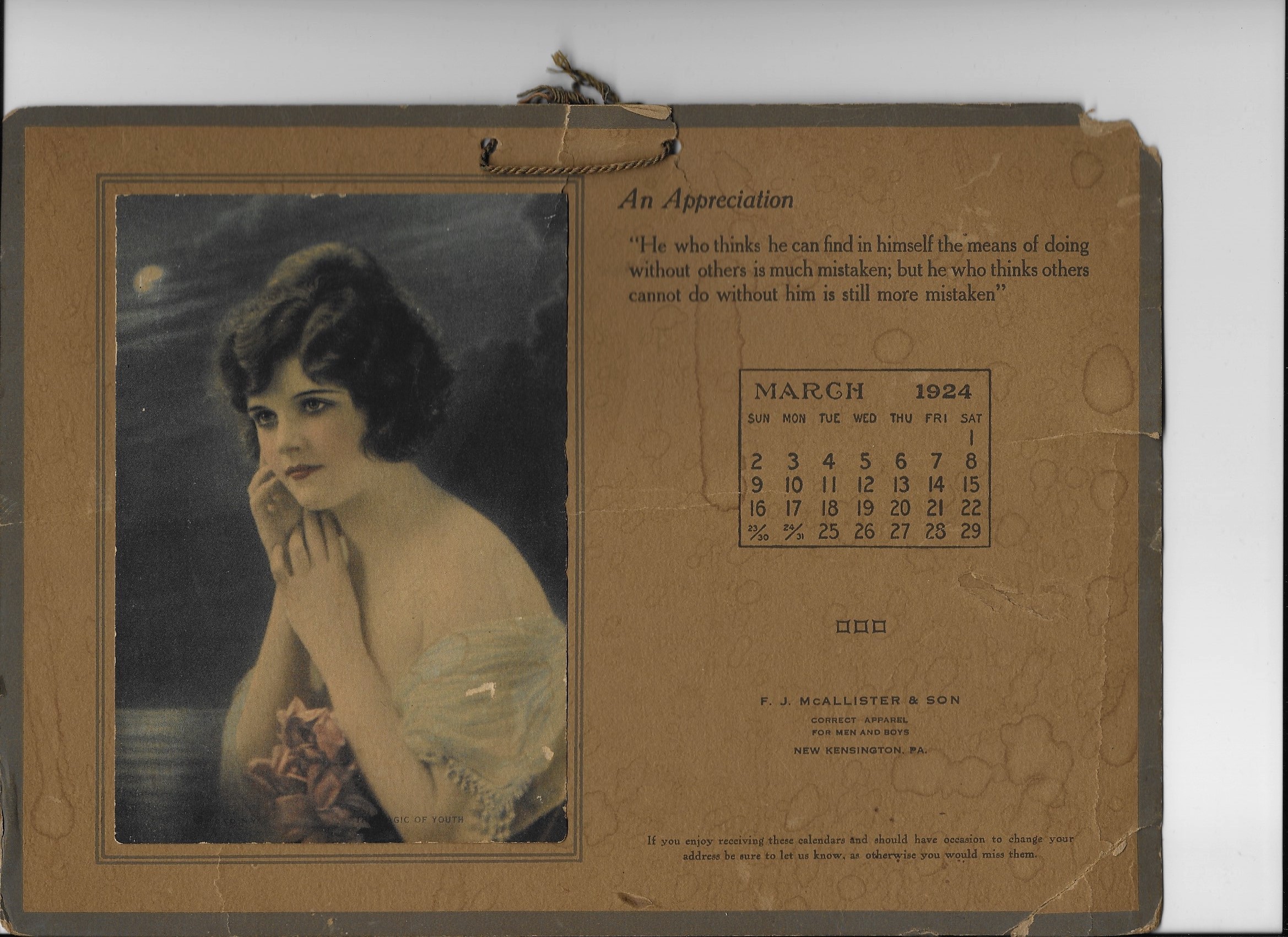

– “The Magic of Youth” found on a 1924 calendar advertising F.J. McAllister & Son Correct Apparel for Men and Boys, New Kingston, PA. The original photo from which this print originated is part of the Tonnesen Archive of the Winneconne Historical Society, Winneconne, Wisconsin.

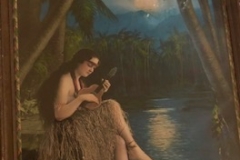

– This “bio” of the model in “The Magic of Youth” is almost certainly fictional. The print on the calendar lifts up to reveal it underneath. These modest, but glamorous, “pre-pinup” era prints of beautiful women were sometimes accompanied by romanticized biographies, probably concocted by the publisher’s copywriters, portraying the models as non-professional, girl-next-door types that the advertiser’s mostly male clientele could dream of meeting in real life. And Tonnesen worked out of her studio in Chicago, not the Pacific Coast, and was known to use local models.

Copyright 2017 Lois Emerson

Have We Found Yet Another Tonnesen Model?

|

|

|

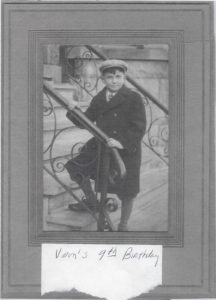

Back in December of 2008, we reported that Chicagoan Jane Berghauer (1916-1994) had been identified as the blond toddler in images by Beatrice Tonnesen circa 1917-1920. Jane had a younger brother, Vern (1920-2004), who was also known to have modeled and, since then, I’ve been keeping an eye out for evidence that Vern had modeled for Tonnesen.

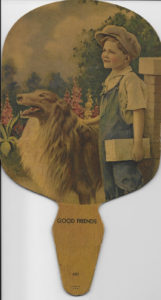

Now, I think I’ve finally found Vern in a pair of images depicting the “boy and his dog” theme so popular in the early part of the last century. I can’t be absolutely sure of either the model’s identity or the identity of the photographer behind the images, but there is strong evidence that Tonnesen was the photographer and Vern Berghauer was the model.

The wavy-haired collie in both images has appeared in at least one confirmed mid-twenties photo by Tonnesen and she is known to have produced other “boy and dog” themed photos. Additionally, the fabric covering the seat in one of the two prints looks to be one she used in other images. And both images can be linked through the identical clothing worn by the boys.

As to the identity of the boy model: Checkout this photo of Vern Berghauer, age 9, kindly provided to me by Vern’s family friends Brenda and Rudy Arreola. What do you think?

Copyright 2017 Lois Emerson